Arsenic in Assinippi

Arsenic in Assinippi, The Trial of Jennie May Eaton for the Murder of Her Husband, Rear Admiral Joseph Eaton

Arsenic in Assinippi, The Trial of Jennie May Eaton for the Murder of Her Husband, Rear Admiral Joseph Eaton

A century ago, the peaceful, picturesque village of Assinippi, Massachusetts, became the focus of national attention after retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Joseph Giles Eaton was found dead in his bedroom. An autopsy revealed the presence of a fatal dose of arsenic. Authorities launched an investigation, and less than three weeks after the admiral’s death they arrested his wife, Jennie May Eaton, for his murder. She later stood trial in Plymouth County Superior Court where an all-male jury decided her fate.

The prominence of the admiral in military and social circles, the scandalous nature of the charges, and the rare indictment of a woman for a capital crime generated extensive press coverage. It was the era of sensationalism when newspapers, all vying to increase their circulations, splashed dramatic headlines, photographs, and sketches across their front pages. The Eaton case captivated people across the country for eight months in 1913.

This book is a nonfictional account of the events leading up to Admiral Eaton’s death, the ensuing investigation and trial, and the tragic aftermath. Newspaper stories, court records, town histories, census returns, vital records, genealogical records, military records, archival manuscripts, and other documentary evidence are among the sources the author used to tell the story of this significant chapter in the nation’s history.

Chapter 1

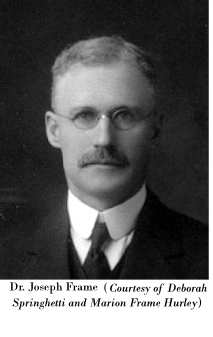

Just before dawn on Saturday, March 8, 1913, Dr. Joseph Frame steered his horse and carriage along Union Street, the main thoroughfare of Rockland, Massachusetts. His thick wool clothing and heavy carriage robe shielded him from the bitter cold as he made his way home from a house call.

Against a chilly gust, he gathered the collar of his overcoat and turned the corner onto Webster Street. When he reached his home at No. 39, his horse instinctively turned and proceeded up the short driveway to the barn. Frame alighted from the carriage and led the horse inside where he unhitched it, led it to a stall, covered it with a blanket, and rewarded it with fresh water and hay. A smile crossed his lips as he retrieved his medical bag from the buggy, closed the barn door, and walked the few steps to the house. He looked forward to the warmth of his hearth and a quiet breakfast with his family.

Entering the house, Frame carried his medical bag into his office and glanced at the clock on his desk. It was 5:50 a.m. At that moment, the telephone rang. When he picked up the receiver, he recognized the voice of Jennie May Eaton.

Jennie, calling from the home of her next door neighbor, Mrs. Herbert Simmons, stunned him with the news that her sixty-six-year-old husband, retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Joseph Eaton, was dead. Frame had examined the admiral at the Eaton home in Assinippi just the day before and prescribed medication to remedy what he had diagnosed as acute gastroenteritis. There was no indication that the admiral’s condition was life-threatening.

Jennie insisted he come to her house right away. It was impossible at the present time, Dr. Frame told her, and there was little he could do for the admiral now. He said he would call on her later. When he asked her for the exact time of her husband’s death, Jennie hesitated. Frame thought this odd. Given her husband’s discomfort, he felt she would have been more attentive. When he pressed her for an answer, she disclosed that the admiral had died about fifty minutes earlier.

Jennie insisted he come to her house right away. It was impossible at the present time, Dr. Frame told her, and there was little he could do for the admiral now. He said he would call on her later. When he asked her for the exact time of her husband’s death, Jennie hesitated. Frame thought this odd. Given her husband’s discomfort, he felt she would have been more attentive. When he pressed her for an answer, she disclosed that the admiral had died about fifty minutes earlier.

When the conversation ended, Frame telephoned Dr. Gilman Osgood of Rockland, the Plymouth County medical examiner, and told him about his visit to the Eaton home the previous day and his concern about the unexpected death. Osgood agreed to meet Frame at the Eaton house at 10:45 a.m. to examine the body.

Before she left the Simmons’ house, Jennie telephoned Norwell undertaker Ernest Sparrell. At about 7:00 a.m., Sparrell and his assistant, Joseph Wadsworth, arrived at the Eaton home. Jennie met the two men at the door and escorted them upstairs to the admiral’s bedroom.

Moments later, Mrs. Simmons came to the Eaton house with a message from Dr. Frame, asking that Sparrell call him from the Assinippi post office. Sparrell summoned Wadsworth and both, puzzled by Frame’s request, immediately walked the short distance to the post office. Just as they arrived, Frame called and asked for Sparrell. When Sparrell took the phone, the doctor briefly explained his concerns about the circumstances of Admiral Eaton’s death. Frame instructed Sparrell to leave the corpse untouched until Dr. Osgood could examine it and asked him to keep the matter confidential.

~

Assinippi Village lies at the crossroads of Webster and Washington streets between the towns of Norwell and Hanover, nearly twenty miles south of Boston. It acquired its name from an ancient spring in the area used by the Wampanoag Indians who called it “Hassen Ippi,” meaning “rocky water.”

Poultry farms dominated the Assinippi landscape in 1913. Poultry and egg production supplied the Boston markets and households throughout the South Shore. Dairy farms in the area produced milk, butter, and cheese, while other farms provided fruits and vegetables.

The village proper, typical of its time, contained a general store, a butcher shop, a wheelwright and blacksmith shop, a cigar shop, and a pool hall. Deliverymen rolled along the village’s unpaved roads carrying their wares of dry goods, flour, sugar, and milk, and specialties like meats, fish, and clams.

Residents of both Norwell and Hanover worshipped at the Universalist Church, located on a hillock with a commanding view of the village. In Union Hall, villagers held minstrel shows, political rallies, business meetings, and an annual harvest festival that drew people from miles around.

The Brockton Street Railway operated a trolley line on Webster Street from the village to Mann’s Corner in North Hanover where passengers could continue to neighboring Rockland for connections by rail or trolley to Boston or Plymouth. At Mann’s Corner, passengers could also board a trolley for busy Queen Anne’s Corner in Hingham and for Nantasket Beach, a popular summer resort in Hull.

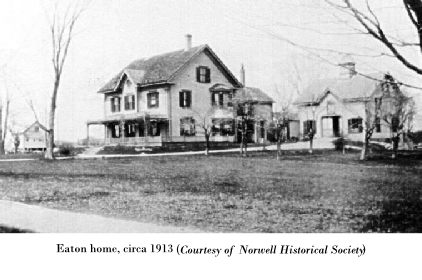

The Eatons’ yellow, two-and-one-half story, ten-room home stood back about a hundred feet from Washington Street on twelve acres of land in Norwell, a half mile north of the village center. The admiral and his wife purchased it from Ella Dunham in July 1907. Built in a Folk Victorian style by Franklin Jacobs in the 1860s, the first floor included a dining room, a sitting room, and a living room with an adjoining library, each with a fieldstone fireplace. Off the dining room was a large kitchen with an ample pantry. Stairways front and back led to four bedrooms and a maid’s quarters on the second floor and a spacious attic above. The rooms were well appointed with “rare and handsome furniture, tasteful carpets, valuable curios from all over the world, and books in abundance, exquisite china, delicate bric-a-brac, and rare pottery from various climes,” the Boston American reported.

The Eatons’ yellow, two-and-one-half story, ten-room home stood back about a hundred feet from Washington Street on twelve acres of land in Norwell, a half mile north of the village center. The admiral and his wife purchased it from Ella Dunham in July 1907. Built in a Folk Victorian style by Franklin Jacobs in the 1860s, the first floor included a dining room, a sitting room, and a living room with an adjoining library, each with a fieldstone fireplace. Off the dining room was a large kitchen with an ample pantry. Stairways front and back led to four bedrooms and a maid’s quarters on the second floor and a spacious attic above. The rooms were well appointed with “rare and handsome furniture, tasteful carpets, valuable curios from all over the world, and books in abundance, exquisite china, delicate bric-a-brac, and rare pottery from various climes,” the Boston American reported.

Adjacent to the house was a large barn that also served as a carriage house. Behind it were the outbuildings typical of a poultry farm – chicken coops, brooder and incubator houses, a packinghouse, and a duck pond.

The inhabitants of this idyllic setting in 1913 were living a less-than-idyllic life. In their newfound grief, they were surely unaware that their private, domestic squabbles were about to become a public spectacle.

~

Dr. Frame first visited the Eaton home in February 1911 when he treated Jennie’s ailing mother, Virginia Harrison, who lived in the house with the Eaton family. Several weeks later, he returned to see Jennie who was bed-ridden with the grippe (influenza). He recommended rest, an analgesic, and a tonic that he sent to her the same afternoon. When he spoke to her the next day, he was glad to hear she was slightly improved but surprised that she had not taken the prescribed medicine because, she said, it had passed through her husband’s hands and she feared he had poisoned it.

Surely she didn’t mean this, Frame thought. Such an idea was preposterous, and he told her so. She was startled by his abruptness. In defense of her claim, she said the admiral was capable of such an act and, furthermore, that he was insane and belonged in an institution.

Frame dismissed her claims. His colleague, Dr. Charles Colgate of Rockland, had counseled him earlier about Jennie’s irrational behavior. Colgate had been the Eatons’ attending physician from 1907 until 1909 when he withdrew his medical services following the tragic death of a child the Eatons had adopted.

Jennie had publicly accused her husband of poisoning the child, and the couple had separated for a brief time. Later, when analysis confirmed that the child had died of natural causes, Jennie returned home. The couple never fully reconciled, and Jennie continued to blame her husband for the child’s death. Her persistent accusations, complaints to Colgate about the admiral’s mental instability, and demands for his institutionalization led the doctor to sever his relationship with the family.

One afternoon in August 1912, Frame went to the Eaton house to treat Admiral Eaton for a stomach complaint. He found the admiral sitting in a wicker chair on the front porch. As the two men conversed, Jennie emerged from the house and declared that her husband’s excessive drug use had caused his illness and had affected his mind. The admiral calmly denied his wife’s assertion.

Frame saw no evidence in his examination to refute the admiral’s contention, nor did Eaton say or do anything to suggest a mental disorder. The doctor prescribed a remedy to quell the admiral’s discomfort and told him to call if the condition persisted.

Several weeks later, Jennie appeared unannounced at Frame’s office. Determined to convince the doctor that her claims about the admiral’s instability were valid, she repeated the concerns she had expressed during the doctor’s earlier visit to her home. She pleaded with the doctor to reexamine Admiral Eaton and have him committed, but Frame refused. He said he had seen nothing during his interaction with the admiral to suggest that he was an addict or in need of institutional care. Frame reiterated his belief that her fears were unfounded. Jennie stormed from the office in exasperation. Why could this doctor not see what was so patently obvious to her?

~

On Saturday, March 1, 1913, Frame went to Assinippi again to see Mrs. Harrison who was complaining of general weakness. He wrote her a prescription and recommended fluids and rest. As he prepared to leave, he assured Mrs. Harrison of a prompt recovery and said he saw no need to return. Admiral Eaton, however, expressed concern about his mother-in-law’s frail health and implored the doctor to look in on her the next week. Frame agreed to do so.

At 8:30 a.m. on the following Friday, Frame called as promised to check on Mrs. Harrison’s progress. He knocked at the side door and, after a brief wait, Jennie answered.

“How fortunate you came, Dr. Frame,” she said. “The admiral has been sick all night.”

Frame followed Jennie to the second floor and found Eaton lying in bed, complaining of excruciating abdominal pain. The admiral told the doctor he had been purging all night after dining on roast pork. He had become sick almost immediately after eating.

“No more roast pork for Joseph,” the admiral woefully remarked to the physician.

The doctor felt that Eaton’s symptoms were consistent with gastroenteritis. He gave the admiral subgalate of bismuth tablets and instructed him to continue with the bismuth and take limewater or saleratus (sodium bicarbonate) as he improved.

Frame left the admiral and went to Mrs. Harrison’s room. She was still in bed, but her condition had noticeably improved. He advised her to stay in bed and continue with the medicine he had prescribed, then he departed for his office.

~

Frame arrived at the Eaton home some five hours after Jennie had called him to report the admiral’s death. He met Jennie at the front door and went with her to the admiral’s bedroom where he found the undertakers Sparrell and Wadsworth and Jennie’s daughter, Dorothy, conversing quietly. Frame saw the admiral’s corpse lying in a supine position at the edge of the bed. He noted moist vomit on the sheet in the center of the mattress.

Jennie told Frame that her husband had continued to purge throughout the night. His retching had prevented him from retaining the medicine the doctor had prescribed. She had done her best to make him comfortable and, after he had fallen asleep, she had retired to Dorothy’s bedroom.

At about two thirty in the morning, Jennie’s mother had roused her and Dorothy to tell them the admiral had fallen. They had gone to his room and found him sitting on the floor against the bed. They had helped him to a chair, changed his nightclothes and his bed linens, and assisted him back to bed. Jennie had then sent Dorothy back to her room, had laid down next to the admiral and quickly fallen asleep. She had awoken just before dawn and found him cold to the touch.

After hearing Jennie’s report, Frame left the admiral’s room and went down the hall to see Mrs. Harrison. She was still indisposed and appeared visibly shaken by the admiral’s death. She told the doctor how she had heard the admiral fall from his bed during the night and how perplexed and saddened she was by his astonishing demise.

The doctor briefly examined her. Satisfied with her progress, he told her to continue with fluids and rest and started out of the room. At the threshold, he stopped abruptly, turned to Mrs. Harrison, and said, “There’s something behind all this.” She lay in stunned silence, bewildered by his remark. A sense of foreboding engulfed her and, as she watched the doctor depart, the frail, frightened woman wept.